Iranian students and faculty at York are notably concerned about the unprecedented spike of capital punishment in Iran and call for action.

“As the Iranian regime continues its diplomatic push abroad, it has continued to wage a war at home, targeting those who dare to defy its rule, particularly ethnic minorities who have formed an organized resistance,” says York political science student Saeed Valadbaygi.

Most recently, Iranian officials lambasted the Sunni Kingdom for executing Sheikh Nimr al-Nimr, the prominent voice of the country’s Shia minority. In Tehran, a furious mob stormed and set fire to the Saudi Embassy, and the Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei called on “divine vengeance.”

Ironically in 2015, Iran executed dozens of regime’s political dissidents belonging to different ethnic and religious minorities, including 15 Kurdish and three Baloch political prisoners.

According to Valadbaygi, the soaring number of execution of Kurdish political prisoners is just an example of Iran’s systematic war against ethnic minorities, including Arabs, Azeris, Baloch, and Kurds.

Last year, Iran executed more individuals per capita than any other country in the world, and with more than 1,000 executions recorded, the highest rate of capital punishment of the country in the last 25 years. The number is equivalent to executing more than three people per day.

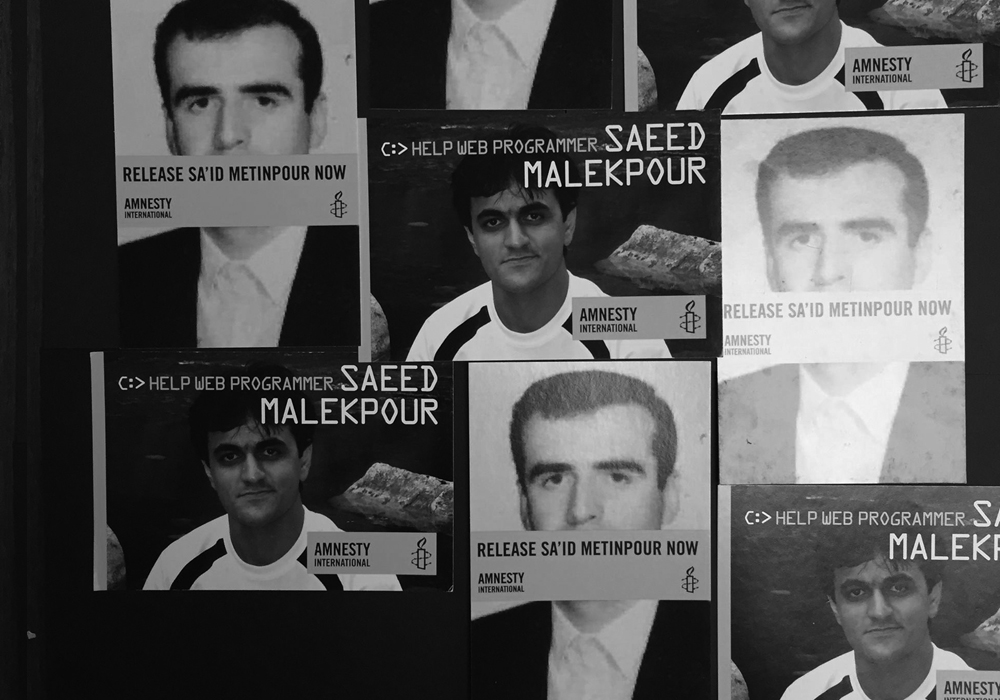

“The grotesque surge in executions in Iran is even more appalling when one considers how broadly its applied and its use in creating a state of fear,” says Jessa McLean, president, Amnesty International at York.

“Those prisoners who are still on death row need us to speak up now, as the situation seems to be getting worse.”

In a report presented to the United Nations General Assembly on October 27, Ahmed Shaheed, the special rapporteur on the human rights situation in Iran, said the majority of executions violate international laws and called on Iran to impose a moratorium on the death penalty for all but the “most serious crimes.”

According to the U.N. 69 per cent of individuals who were put to death during the first six months of 2015 were reportedly for narcotic-related offences, and the rest were related to murder, adultery, armed robbery, and Moharebeh (waging war against God), a charge that is commonly raised again political prisoners.

Human Rights Watch reported that laws of which ‘political prisoners’ being punished by are vague and broadly worded. “Iranian Shari’a laws criminalize the exercise of fundamental rights and allow the authorities to punish a range of peaceful activities and free expression with the legal cover of protecting national security,” reads the HRW report.

Rights groups believe that the Iranian Islamic Penal Code that is based on Sharia law provides enough tools for stifling regime’s political opponents.

“Iranian authorities have their own interpretation of Shari’a law that is based on Jafari jurisprudence.

According to their interpretation, questioning the Guardianship of the Islamic Jurists and the Supreme Leader is a criminal act,” York professor Minoo Derayeh told Excalibur.

According to Derayeh, Iranian judiciary system is not independent and when it comes to political prisoners’ cases, the security institutions have the final say.

The provisions of Iranian constitution added in 1989 mandating lawmakers to define “political offenses” and demands that the perpetrators of such offences should be tried before a jury. No law containing such provisions exists and many prisoners were convicted in trial where basic rights such as access to a lawyer were ignored.

It’s commonly reported that prosecutors relied primarily on confessions that are obtained through physical and psychological coercion and torture, and failed to provide any other convincing evidence establishing the defendant’s guilt. It’s documented that in cases related to the so-called ‘national security,’ sometimes the prisoners’ charges were totally unrelated to the charge that had landed them in prison, and their trials had lasted less than five minutes.

Iran’s revolutionary courts are notorious among human rights activists as venues where verdicts are set before trials take place.

“In the case of political prisoners, the court proceedings are ceremonial and sentences are preordained,” said Derayeh.

The number of political prisoners in Iran remained unknown. In March 2014 the U.N. Human Rights Council estimated that “at least 895 ‘prisoners of conscience’ and ‘political prisoners’ were reportedly imprisoned in the Iranian prisons. The Iranian Judicial authorities, however, continuously rejected the claim and called such assertions “a very big lie.”

According to Reporters Without Border, with 65 journalists and netizens in prison – five of them foreign nationals – Iran is one of the world’s top five prisons for those working in news and information.

On Saturday, Iranian State media reported the release of four dual citizen prisoners, including famed Washington Post correspondent Jason Rezaian, who was arrested back in 2014 on alleged charges of espionage.

The release comes as part of the U.S led negotiations with Iran regarding their nuclear deal and subsequent ease of sanctions. In exchange, the U.S will drop or pardon charges against seven Iranians that were accused of violating U.S sanctions.

Former U.S. Marine Amir Hekmati, pastor Saeed Abedini and Nosratollah Khosravi-Roodsari, along with Rezaian were flown to the U.S via Switzerland.

Hajir Sharifi, Contributor