Alex Wagstaff

Copy Editor

It’s a tough world for old-fashioned physical movie stores.

Some are failing. Blockbuster Canada is ceasing all its operations at the end of the year. Rogers and Movie Gallery are following suit and have already shut down swathes of stores across Canada.

So, why are the massive corporate chains faltering?

Netflix, mostly. The service makes up about a quarter of North American web traffic and is earning scads of money—income last quarter was up 57 per cent from the same time last year. Besides popularity, it even has a pretty good library—in the US, anyways.

For less than 10 dollars a month, there really is no better way to fill up on movies. No wonder the big chains are going out of business.

But while the national video empires crumble, local stores are surviving. Queen Video, an independent downtown rental shop, is doing just fine, despite facing the same problems as the major chains.

The difference is that stores like Queen Video understand what they can offer that Netflix can’t: selection.

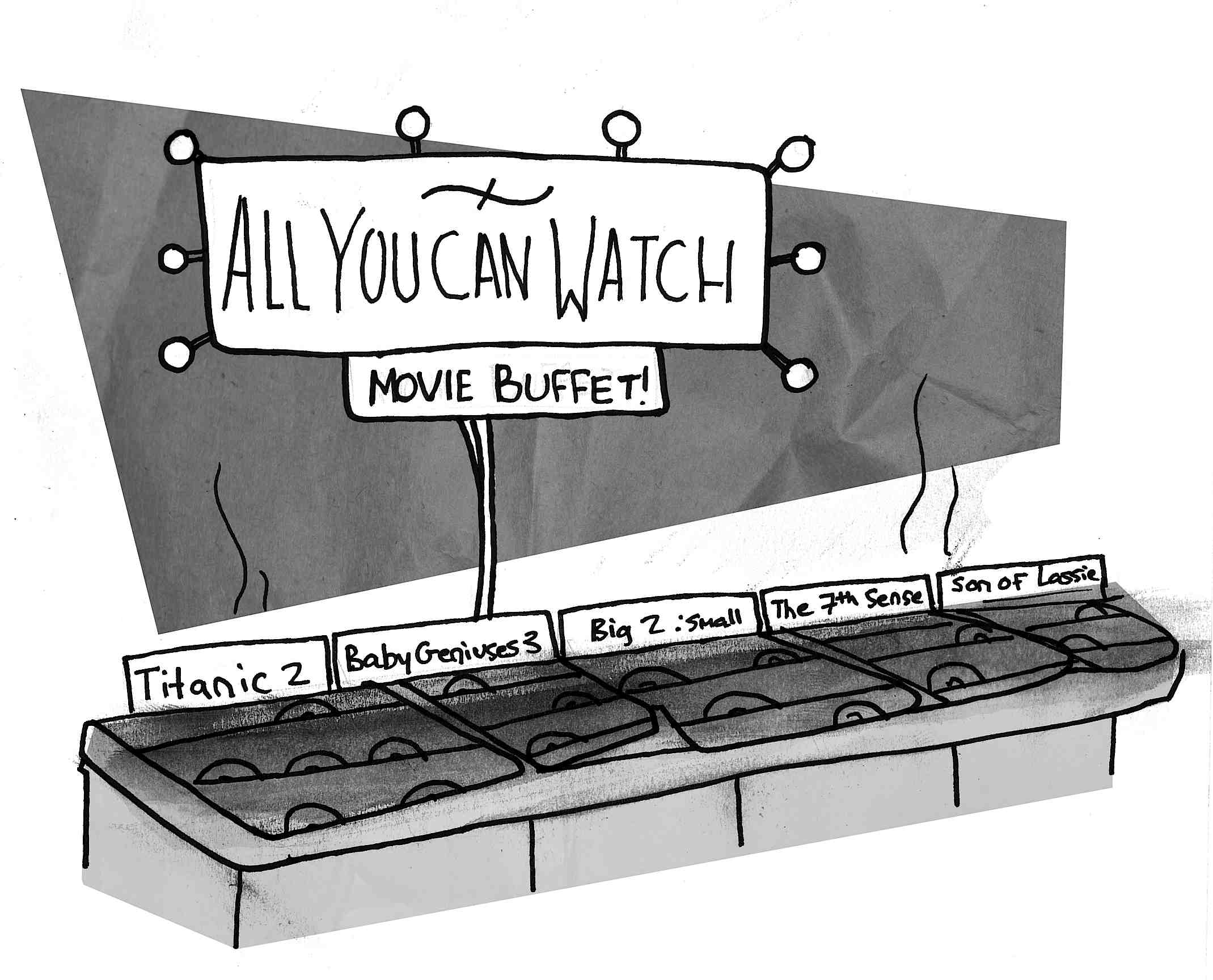

Like a buffet, Netflix serves up as many films as you want, and also like a buffet, there’s no guarantee that you’ll find anything you really want. A bricks-and-mortar store, on the other hand, depends on the strength of its stock. When customers pay for each movie, they incur more expenses. They get pickier.

It’s kind of a shame to think of the squandered opportunity.

In theory, digital streaming should offer unlimited variety. Distribution costs are nil and there’s no stock to sit on, so there’s no practical reason that an obscure cult classic should be any harder to deliver than last year’s summer hit.

Netflix has plenty of movies that neither Blockbuster nor Queen Video ever carried, but we’re not talking about hidden masterpieces, unless you thought Titanic II was a classic. Because Netflix charges a subscription fee, it really has no motive to improve its library as long as the fee remains low enough to draw customers.

And with licensing as strict as it is, there’s still no hope in the online realm. Until services like Netflix can manoeuvre their way through Canada’s copyright laws, they couldn’t deliver obscure flicks even if they wanted to. Ignoring legal options like Netflix leaves you with torrents, a free, if dodgy, trove of cinematic treasure. But even that approach sometimes doesn’t work. There’s nothing worse than finding out the torrent you need has no seeds.

Stock isn’t just what makes video stores tick. It’s what makes them important, and it’s why their loss is ours, too. Every time a video store closes down, we lose another library of films. The disappearance of physical video stores hurts the consumer by robbing us of choices, from the foreign to the independent, the avant-garde to the obscure.

Unless we keep these stores alive, in time, some movies will simply become unavailable. We’re lucky here at York to have such a comprehensive variety at Scott Library. But everybody else—and someday us when we move on from York—will lose out.