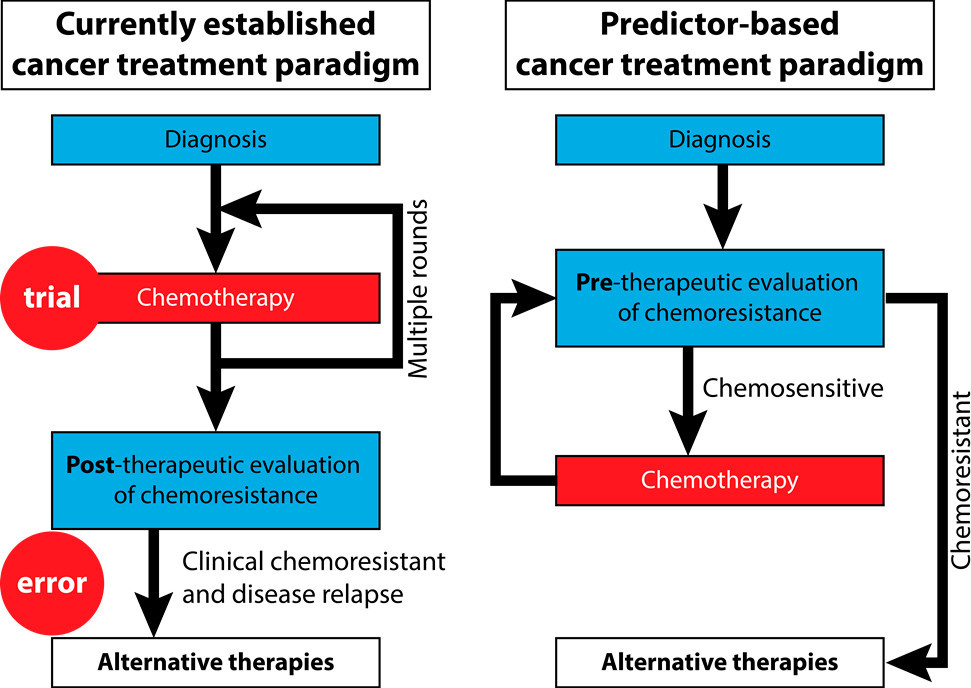

Chemotherapy is the most common and widely known type of cancer treatment. It is, however, not always the best approach for all patients. Dr. Sergey Krylov, a chemistry professor and researcher at York, is conducting groundbreaking research into chemoresistance, which would help predict whether or not cancer patients will resist chemotherapy and tailor their treatment plans to match.

Some patients may have a pre-existing resistance to chemotherapy, or their tumour may develop a resistance to it over time. Ways to predict this chemoresistance have been sought after by researchers for decades, but there simply haven’t been many reliable methods for most types of cancer. Krylov’s research may be part of the answer.

Research into predictors for ovarian cancer is where Krylov begins. “The reason for choosing ovarian cancer is that we anticipate great potential benefits for patients. Currently, near 3,000 women are annually diagnosed with ovarian cancer in Canada,” he says.

According to Krylov, most of these women are treated with a chemotherapy drug called platinum-taxane, which also has severe side effects. As of now, 25 per cent of the women treated with chemotherapy experience chemoresistance.

“Ovarian cancer is a very deadly disease, and chemoresistance is an important contributor to the low survival rate of patients in the advanced stages. Developing methods to detect chemoresistance will help doctors choose the appropriate treatments for patients,” adds York biology professor Chun Peng, who is working in collaboration with Krylov.

Their research has determined the best strategy to measure the population of drug-resistant cells. Determining the amount of cells in the body that are drug-degrading and drug-extruding will provide a better understanding of how to treat someone with ovarian cancer.

Currently, the research is undergoing a feasibility study to determine the likelihood of completing the research successfully.

Krylov’s future plans are to apply his research to a clinical setting. “We will apply this technology for identification and validation of a predictor of ovarian cancer chemoresistance to primary platinum/taxane chemotherapy, which is the first-line treatment for all patients with advanced ovarian cancer.”

Krylov and his team have been carrying out this research for 10 years, and his team has made major advancements. Working with the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre, they have the opportunity to study and apply their research to tissues from various ovarian cancer patients, which will play a role in further developing predictors.

While the predictors for ovarian cancer patients are major discoveries, they are not applicable to other types of cancers. However, they hope to change this soon.

“We are developing a new technology for development of chemoresistance predictors. It will be applicable to all cancers, in which chemoresistance is driven by drug extrusion from cells and drug degradation,” says Krylov.

Krylov and his team’s research could be revolutionary, but he warns that the process will be a group effort. In an interview with Brainstorm, Krylov urged other researchers to join in: “I hope I can convince a good group of researchers to join us; I hope to create a little wave, and that the wave would grow, and more and more people would join this effort.”

To read the research article, visit the website here.