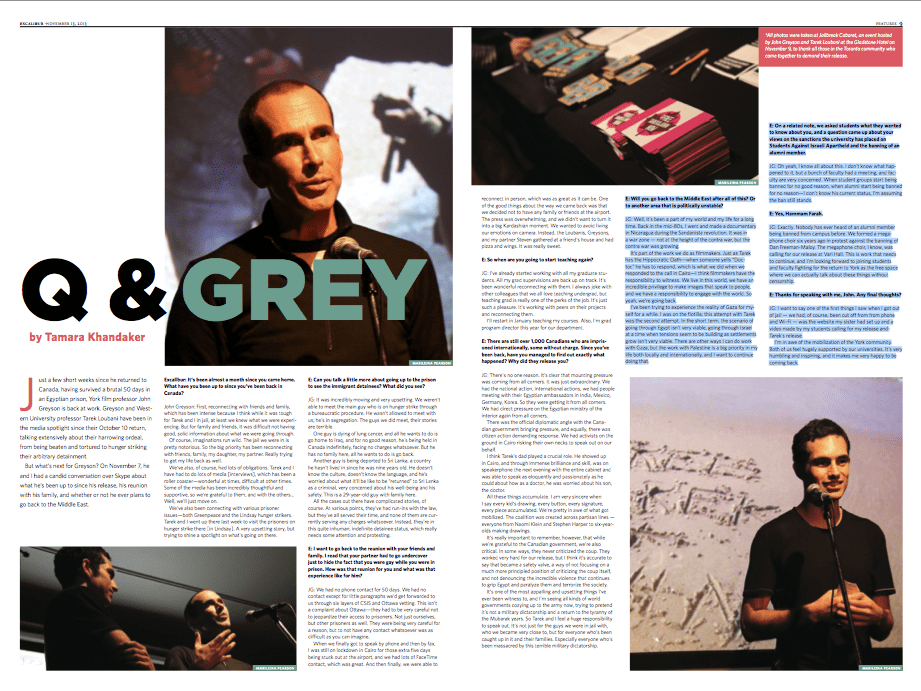

Just a few short weeks since he returned to Canada, having survived a brutal 50 days in an Egyptian prison, York film professor John Greyson is back at work. Greyson and Western University professor Tarek Loubani have been in the media spotlight since their October 10 return, talking extensively about their harrowing ordeal, from being beaten and tortured to hunger striking their arbitrary detainment. But what’s next for Greyson? On November 7, he and I had a candid conversation over Skype about what he’s been up to since his release, his reunion with his family, and whether or not he ever plans to go back to the Middle East.

Excalibur: It’s been almost a month since you came home. What have you been up to since you’ve been back in Canada?

John Greyson: First, reconnecting with friends and family, which has been intense because I think while it was tough for Tarek and I in jail, at least we knew what we were experi- encing. But for family and friends, it was difficult not having good, solid information about what we were going through. Of course, imaginations run wild. The jail we were in is pretty notorious. So the big priority has been reconnecting with friends, family, my daughter, my partner. Really trying to get my life back as well.

We’ve also, of course, had lots of obligations. Tarek and I have had to do lots of media [interviews], which has been a roller coaster—wonderful at times, difficult at other times. Some of the media has been incredibly thoughtful and supportive, so we’re grateful to them, and with the others… Well, we’ll just move on.

We’ve also been connecting with various prisoner issues—both Greenpeace and the Lindsay hunger strikers. Tarek and I went up there last week to visit the prisoners on hunger strike there [in Lindsay]. A very upsetting story, but trying to shine a spotlight on what’s going on there.

JG: It was incredibly moving and very upsetting. We weren’t able to meet the main guy who is on hunger strike through a bureaucratic procedure. He wasn’t allowed to meet with us; he’s in segregation. The guys we did meet, their stories are terrible.

One guy is dying of lung cancer, and all he wants to do is go home to Iraq, and for no good reason, he’s being held in Canada indefinitely, facing no charges whatsoever. But he has no family here, all he wants to do is go back. Another guy is being deported to Sri Lanka, a country he hasn’t lived in since he was nine years old. He doesn’t know the culture, doesn’t know the language, and he’s worried about what it’ll be like to be “returned” to Sri Lanka as a criminal, very concerned about his well-being and his safety. This is a 29-year-old guy with family here.

All the cases out there have complicated stories, of course. At various points, they’ve had run-ins with the law, but they’ve all served their time, and none of them are cur- rently serving any charges whatsoever. Instead, they’re in this quite inhuman, indefinite detainee status, which really needs some attention and protesting.

E: I want to go back to the reunion with your friends and family. I read that your partner had to go undercover just to hide the fact that you were gay while you were in prison. How was that reunion for you and what was that experience like for him?

JG: We had no phone contact for 50 days. We had no contact except for little paragraphs we’d get forwarded to us through six layers of CSIS and Ottawa vetting. This isn’t a complaint about Ottawa—they had to be very careful not to jeopardize their access to prisoners. Not just ourselves, but other prisoners as well. They were being very careful for a reason, but to not have any contact whatsoever was as difficult as you can imagine.

When we finally got to speak by phone and then by fax, I was still on lockdown in Cairo for those extra five days being stuck out at the airport, and we had lots of FaceTime contact, which was great. And then finally, we were able to reconnect in person, which was as great as it can be. One of the good things about the way we came back was that we decided not to have any family or friends at the airport. The press was overwhelming, and we didn’t want to turn it into a big Kardashian moment. We wanted to avoid living our emotions on camera. Instead, the Loubanis, Greysons, and my partner Steven gathered at a friend’s house and had pizza and wings. It was really sweet.

JG: I’ve already started working with all my graduate students. All my grad supervisions are back up on track. It’s been wonderful reconnecting with them. I always joke with other colleagues that we all love teaching undergrad, but teaching grad is really one of the perks of the job. It’s just such a pleasure. It’s working with peers on their projects and reconnecting them.

I’ll restart in January teaching my courses. Also, I’m grad program director this year for our department.

E: There are still over 1,000 Canadians who are impris- oned internationally, some without charge. Since you’ve been back, have you managed to find out exactly what happened? Why did they release you?

JG: There’s no one reason. It’s clear that mounting pressure was coming from all corners. It was just extraordinary. We had the national action, international actions, we had people meeting with their Egyptian ambassadors in India, Mexico, Germany, Korea. So they were getting it from all corners. We had direct pressure on the Egyptian ministry of the interior again from all corners.

There was the official diplomatic angle with the Cana- dian government bringing pressure, and equally, there was citizen action demanding response. We had activists on the ground in Cairo risking their own necks to speak out on our behalf. I think Tarek’s dad played a crucial role. He showed up in Cairo, and through immense brilliance and skill, was on speakerphone the next evening with the entire cabinet and was able to speak as eloquently and passionately as he could about how as a doctor, he was worried about his son, the doctor. All these things accumulate.

I am very sincere when I say every kid’s drawing, every button, every signature, every piece accumulated. We’re pretty in awe of what got mobilized. The coalition was created across partisan lines — everyone from Naomi Klein and Stephen Harper to six-year-olds making drawings.

It’s really important to remember, however, that while we’re grateful to the Canadian government, we’re also critical. In some ways, they never criticized the coup. They worked very hard for our release, but I think it’s accurate to say that became a safety valve, a way of not focusing on a much more principled position of criticizing the coup itself, and not denouncing the incredible violence that continues to grip Egypt and paralyze them and terrorize the society.

It’s one of the most appalling and upsetting things I’ve ever been witness to, and I’m seeing all kinds of world governments cozying up to the army now, trying to pretend it’s not a military dictatorship and a return to the tyranny of the Mubarak years. So Tarek and I feel a huge responsibility to speak out. It’s not just for the guys we were in jail with, who we became very close to, but for everyone who’s been caught up in it and their families. Especially everyone who’s been massacred by this terrible military dictatorship.

JG: Well, it’s been a part of my world and my life for a long time. Back in the mid-80s, I went and made a documentary in Nicaragua during the Sandanista revolution. It was in a war zone — not at the height of the contra war, but the contra war was growing.

It’s part of the work we do as filmmakers. Just as Tarek has the Hippocratic Oath—when someone yells “Doctor,” he has to respond, which is what we did when we responded to the call in Cairo—I think filmmakers have the responsibility to witness. We live in this world, we have an incredible privilege to make images that speak to people, and we have a responsibility to engage with the world. So yeah, we’re going back.

I’ve been trying to experience the reality of Gaza for my- self for a while. I was on the flotilla; this attempt with Tarek was the second attempt. In the short term, the scenario of going through Egypt isn’t very viable, going through Israel at a time when tensions seem to be building as settlements grow isn’t very viable. There are other ways I can do work with Gaza, but the work with Palestine is a big priority in my life both locally and internationally, and I want to continue doing that.

JG: Oh yeah, I know all about this. I don’t know what happened to it, but a bunch of faculty had a meeting, and faculty are very concerned. When student groups start being banned for no good reason, when alumni start being banned for no reason—I don’t know his current status, I’m assuming the ban still stands.

E: Yes, Hammam Farah.

JG: Exactly. Nobody has ever heard of an alumni member being banned from campus before. We formed a mega- phone choir six years ago in protest against the banning of Dan Freeman-Maloy. The megaphone choir, I know, was calling for our release at Vari Hall. This is work that needs to continue, and I’m looking forward to joining students and faculty fighting for the return to York as the free space where we can actually talk about these things without censorship.

E: Thanks for speaking with me, John. Any final thoughts?

JG: I want to say one of the first things I saw when I got out of jail — we had, of course, been cut off from from phone and Wi-Fi — was the website my sister had set up and a video made by my students calling for my release and Tarek’s release. I’m in awe of the mobilization of the York community. Both of us feel hugely supported by our universities. It’s very humbling and inspiring, and it makes me very happy to be coming back.

Editor-In-Chief