Steven Arrol

Contributor

On September 6 the shortlist for this year’s Man Booker Prize was announced. Will Canada have a chance to celebrate local talent this year?

The Man Booker Prize is awarded yearly to the best original novel, written in English, by a citizen of the Commonwealth of Nations, Ireland, or Zimbabwe. With American writers having exclusive rights to the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, the PEN/Faulkner award, and countless other prizes, the Man Booker is generally considered the most important literary award for non-American writers.

Along with respect and recognition from the literary community, the winner of the Man Booker is almost guaranteed a much larger—and international—reading audience, as well as an immediate spike in book sales.

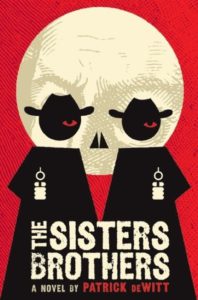

Two Canadian writers made this year’s shortlist. Patrick deWitt and Esi Edugyan are both contenders for the Man Booker Prize, but the biggest buzz surrounds deWitt. The British-Columbia-born writer is impressing critics and readers alike with his sophomore offering, The Sisters Brothers.

It is a funny, sinister, and at times emotional western tale about two brothers, Eli and Charlie (last name “Sisters”), who are being paid to travel from Oregon to Sacramento to find and kill a man named Herman Kermit Warm. Set during the early days of the American gold rush, deWitt manages to bring these two assassins to life, using their disagreements and the strange characters they encounter along the way to offer poignant reflections on identity and morality, among other themes.

Eli’s blunt first-person narration provides humour during times of violence and cruelty, making deWitt’s novel a genre-bending dark comedy. At times the plot, setting, and characters evoke images of last year’s film True Grit, with Eli and Charlie’s strange but endearing relationship, resembling that of Jeff Bridges and Matt Damon.

But deWitt still has to create his characters from scratch, and The Sisters Brothers does not come without criticism. Readers may initially be put off by what seems to be lack of emotion in the narrator’s tone, which could potentially isolate deWitt’s audience from his characters and discourage a full read-through.

But one has to take into account the fact that Eli is a hitman for hire, living in a time when the strong, silent type was the only type a man could be, and “survival of the fittest” was very much a literal interpretation. It needs to be stressed that deWitt is in no way a poor man’s Hemingway, and The Sisters Brothers is in no way a boring read. In fact, as the story unravels, Eli expresses his true feelings about his line of work, inviting readers into his world and revealing his damaged-but-not-yet-broken moral compass.

The only question is whether or not deWitt’s western is enough to impress the Man Booker judging panel; known for their occasionally dry preference, the judges may view The Sisters Brothers as simply clever genre-fiction—a book that, because of its ability to entertain, must surely lack enough depth to be considered “literary fiction”.

On the other hand, the judges may commend deWitt’s attempt at bridging the large and unfortunate gap between today’s plot-driven bestsellers (commonly devoid of social commentary and insight into the human condition), and critically acclaimed character-driven novels (which sometimes become soap-boxes for the author’s long-winded rants, completely forgetting the reader’s attention span).

It remains to be seen if Patrick deWitt will win the Man Booker Prize this year, but one thing is for certain: he is a writer to watch, one whom Canadian readers should be proud of.