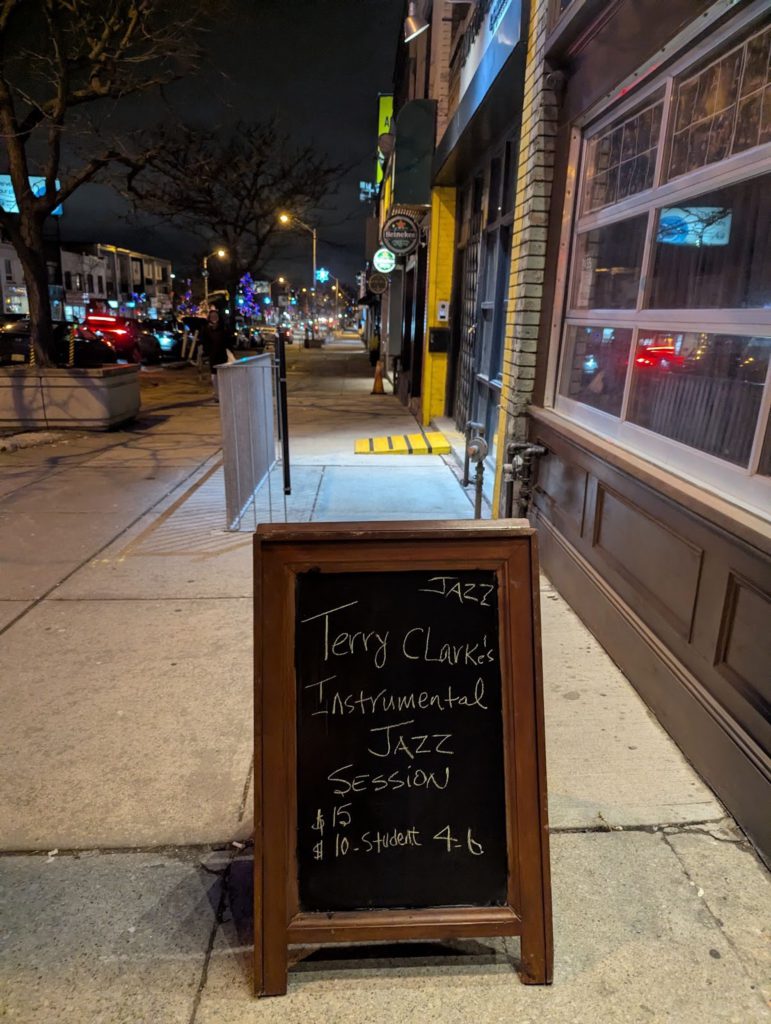

Hirut Restaurant and Café, located near Woodbine station, has spent nearly two decades providing locals with Ethiopian food and a space for Toronto’s live music scene. Owned by its namesake, Hirut, as well as Tibebe and their family, the café was established in 2009 and calls itself “Toronto’s Listening Room.” Hirut Café features new and well-known musicians, as well as monthly comedy shows, in a warm and intimate space. On Sunday, Jan. 11, the café was warmer than ever, packed tightly with musicians and musicophiles who came to watch Toronto-based drummer Terry Clarke lead a jazz improv session.

Born in 1944 in Vancouver, B.C., Terry Clarke began his music career as a teenager drumming in a rock-and-roll duo with his brother. In the ‘60s, Clarke moved to San Francisco and formed a band with American lead alto saxophonist John Handy and Canadian multi-instrumentalist Don Thompson. Clarke stayed there for three years before returning to Vancouver when the Vietnam War pushed him and his band members out of the country. In the late 1960s, he moved back to the U.S. and joined a pop group called The 5th Dimension, whose song “Don’t Cha Hear Me Callin’ to Ya” was featured in the documentary Summer of Soul (…or, When the Revolution Could Not be Televised), a music film that captures the Harlem Cultural Festival of summer 1969, where thousands of people gathered to celebrate Black history and culture. Filmed over the course of six weeks in 1969 by American drummer and producer Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, Summer of Soul was released in 2021 and was recognized with several awards, including the Academy Award for Best Documentary.

Eventually, Clarke’s U.S. work permit expired, and he moved back to Toronto with plans of getting his papers in order and quickly returning to New York. Clarke’s return to the States ended up only being quick on the cosmic scale. “I moved to Toronto while I was waiting for all this to happen, and then I ended up staying in Toronto for 15 years!” Clarke said with a laugh. The 1970s marked the beginning of the Canadian Content regulations, which required radio stations to have 30 per cent Canadian music. A song would count towards this quota if at least two of the following credits were Canadian: music, artist, performance, or lyrics. This criteria provided a career-defining opportunity for Clarke and his band members, who spent as much time as possible in the studio producing content to fill the gap.

Clarke reminisced on this 15-year period as “a really incredible time.” In 1985, he was finally able to move to New York, where he spent another 15 years. “And then I moved to Toronto again in 2000, with a family. I met my wife in New York, and I have seven grandkids, and they’re driving me crazy!” Clarke exclaimed jokingly.

Just before hosting the jazz session at Hirut, Clarke had spent three weeks in Germany playing shows with Canadian-born and Brooklyn-based vibraphone player, Stefan Bauer. “[Jazz is] treated like classical music in Europe and Japan,” Clarke stated while reflecting on his recent travels. “They don’t talk — they sit and listen to what you’re doing. As a matter of fact, the other night was a very quiet audience. I couldn’t believe how focused everybody was,” he added in reference to the most recent jazz session at Hirut. “It shocked me coming back from three weeks of concerts in Europe, where you can hear a pin drop while you’re concertizing, to have that happen here.”

The Terry Clarke jazz sessions began a year ago when Clarke suggested to the owners that Hirut Café host weekly improv nights on Wednesdays, in a similar vein to the weekly jam sessions held at the Jazz Bistro near Toronto Metropolitan University and the Rex near University of Toronto St. George. “That’s how musicians get to know each other,” Clarke explained. “You go where the music is.” During Clarke’s tour in Germany, he encountered audience members that knew of Hirut. “It’s an international language. We’re talking to each other with notes—in musical ideas—and we’re bouncing ideas back and forth. It’s just a big conversation: a musical conversation.”

Allison Au — a local alto saxophonist, composer, and music professor who played on stage with Clarke on January 11 — said that when she thinks of jazz, she thinks of freedom. She attributed this association to the history of the genre’s development, remarking that “it comes from a lot of hardship and turmoil and disparity. So I think jazz today in essence still has that…It’s a music genre that celebrates the individual through featured solos, but it’s also very much like a team sport because you can’t do it without other people…it’s freedom, but also community.” Having studied jazz theory, harmony, and improv at Humber College, Au has spent a lot of time practicing her instrument on her own. But when she comes to spaces like Hirut Café, jazz goes from being a solitary activity to one that bridges all kinds of communities, cultures, and conversations.

Regarding the future of Toronto’s local jazz scene, Au says that “the thing that jazz struggles with today is, if you go to a typical jazz festival, for the most part, it’s still mostly older listeners. And I think the genre is struggling to find ways to include younger people.” Clarke, on the other hand, thinks that jazz has struggled with changes in the media — such as the shift from print to phones — but that post-COVID, many people are “thirsty” for live music, as seen by the packed room at Hirut. “We’ve always been fighting to legitimize jazz since it started,” Clarke says. “The other night was a small snippet of the history of the music…And if you love music, you never stop loving music. That’s why I’m still here.”

Clarke was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2001 in recognition of his outstanding musical achievement, artistry, and impact. Learn more about Terry Clarke here, or swing by his jam sessions at Hirut Café every other Sunday.