Since May 2022, climate change activists around the world have been gluing themselves to famous paintings to draw attention to the reality of climate change. This past October, activists also began throwing various substances on paintings.

On Oct. 14, in London’s National Gallery, two climate change activists from Just Stop Oil threw tomato soup at Vincent van Gogh’s Fifteen Sunflowers. Then, on Oct. 23, in Potsdam’s Museum Barberini, two activists from the Letzte Generation (Last Generation) threw mashed potatoes at Claude Monet’s Haystacks.

Throwing liquids spread to North America as two activists from the environmentalist group, Stop Fracking Around, threw maple syrup on Emily Carr’s Stumps and Sky at Vancouver Art Gallery on Nov. 12. While the paintings themselves are not actually damaged because they are covered in protective glass, damage to the surrounding area has certainly made a splash.

Cyrus Moeini-Azad, a fourth-year English student, says that “what activists have been doing as of late seems pathetic. I can commend the willingness, but the execution does nothing but infuriate me and, no doubt, many others.”

Moeini-Azad adds that the strategy of activists gluing themselves to artwork is reminiscent of an earlier strategy of environmental activism in which activists would bind themselves to trees to protest deforestation or construction.

“The act of throwing food onto paintings sullies their intended message,” says Moeini-Azad. “I’ve seen them speak of hunger, yet they have no worries about wasting food for their stunts. The attempt to damage valuable and historic artwork is enough to divert the attention of the people who see them — myself included — away from the message they are trying to convey.”

Samran Muhammad, a first-year MA student in English and an artist, who has dedicated many hours to a single work of art, agrees.

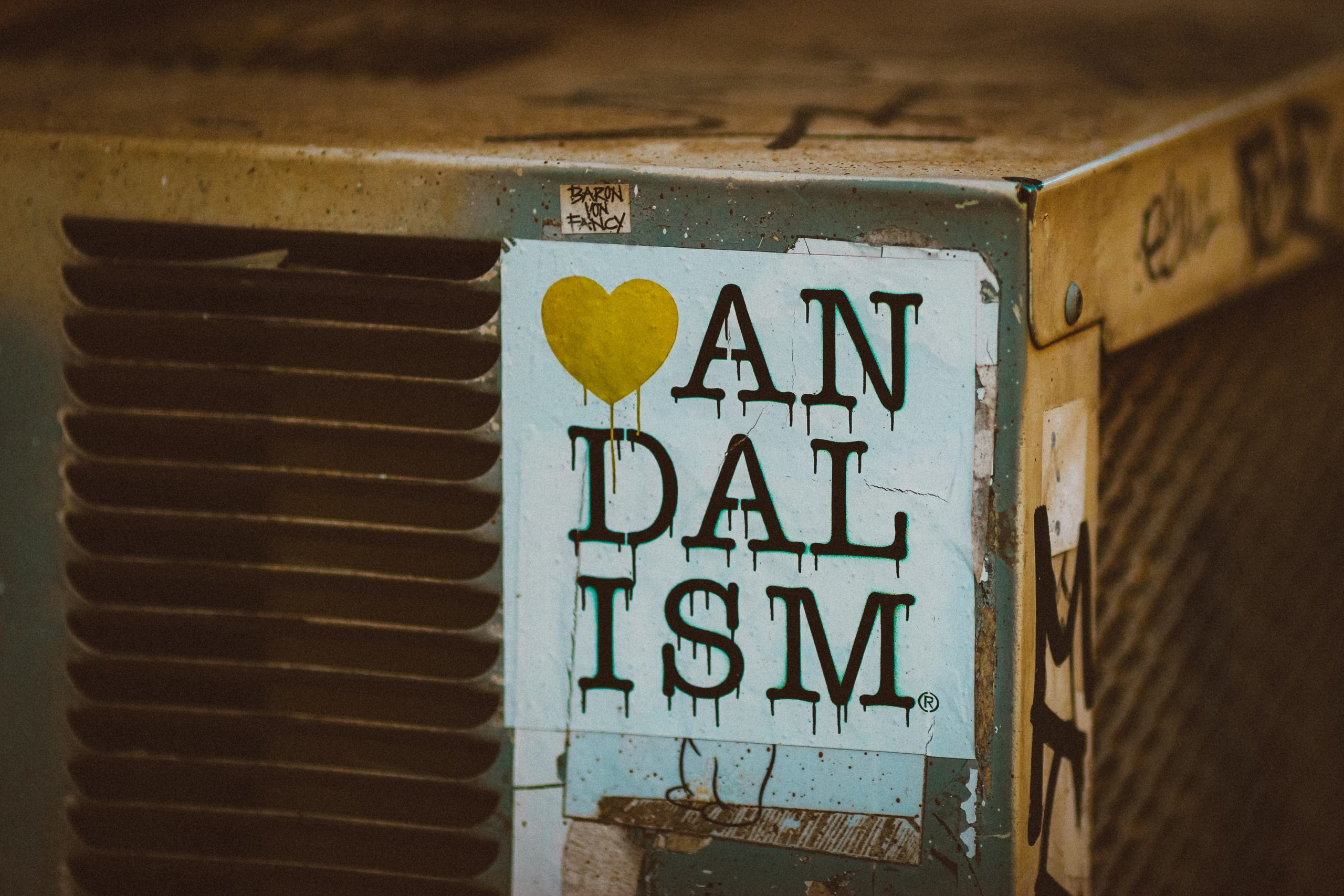

“Raising awareness on a topic that is affecting all of us, and will continue to affect future generations, is definitely needed,” says Muhammad. “It is turning into a shocking performance that is forcing people to look, but as an artist myself, I disagree with the act of vandalism. To finish a piece and observe it in its entirety gives more pleasure to the artist than it does to another person because the artist understands the hours, weeks, and months spent on it,” says Muhammad.

Fourth-year chemistry student, Soroush Fazel-Pour reiterates Moeini-Azad’s and Muhammad’s comments, and thinks that this kind of activism does more harm than good.

“On the one hand, I do feel that the severity of the actions matches the gravity of the climate crisis,” says Fazel-Pour. “On the other hand, the actions are polarizing and distract from the very message the activists are trying to spread.” Fazel-Pour also wonders whether such activism has been “bankrolled by oil companies and other interest groups that benefit from climate inaction”.

Sarah Waithe, a recent graduate in 2020 with an MA in Development Studies, adds that, “targeting famous paintings is an interesting strategy since it raises the question about what lengths activist groups will go to in order to have their voices heard to get the attention of society and leaders.”

Click here to learn more about which historical art pieces have been impacted and to learn more about art vandalism as an act of raising global warming awareness.