While students and recent graduates are not among the groups most physically vulnerable to COVID-19, the pandemic is taking a very real toll on them in other ways. The current job market is demoralizing for new grads and they are struggling to acclimatize and find entry-level jobs.

Canadian youth have been hit particularly hard by the pandemic, as the unemployment rate for 15 to 24 year olds rose from 10.3 per cent in February to a monthly historical high of 29.4 cent in May, just when recent graduates hit the job market. In October, it remained at 18.8 per cent, according to Statistics Canada. As the country moves toward tighter restrictions to fight the spread of COVID-19, job prospects for students seem poised to worsen.

While a vaccine has finally — and thankfully — arrived, Statistics Canada also highlights that the financial implications for this year’s class of high school, college, and bachelor’s degree graduates will be realized over a longer term; for example, individuals within this demographic could lose $25,000 or more in earnings over the next five years. This loss will likely be magnified for recent university grads. The study also concludes that potential losses range from about $23,000 to $44,000, depending on the individual.

Studies such as RBC’s The Recession Roadblock have shown that youth who start their careers in tough economic times will encounter slower career progression than those starting out in a strong economy.

For recent university graduates — who just invested time and money in the expectation of a career boost — this is disheartening news. Poised to start fulfilling their aspirations, many of them have been stopped short and have lost momentum. The pressure to find a job that justifies the cost and time of postsecondary education can lead to anxiety at the best of times, but the social isolation necessitated by COVID-19 compounds these concerns and can present real risks to the mental health of students and grads alike.

Many graduates find themselves abruptly trading the rich social life and stimulation of the university environment for a lockdown at home with their parents, with no job prospects and a bleak market outlook. The blow to morale and the mental health risks cannot be overlooked.

A decade from now, we do not want to be talking about the “COVID generation” that was left behind.

As a society, our recovery strategies must incorporate the mental health and career implications for our youth. Moreover, if we cannot help our youth regain their momentum, we will lose out on the valuable skills and new ideas they could have contributed, and we may see them trapped in temporary, low-paying jobs for a long time to come. A decade from now, we do not want to be talking about the “COVID generation” that was left behind.

So what can be done?

We must look for better ways to coordinate our recovery planning across federal, provincial, and municipal levels. We must have a deliberate plan to integrate employment services with mental health services, and specifically address the unique needs of our youth just embarking on their careers.

Youth access to mental health services and employment services can be facilitated and, optimally, be made more seamless. Traditional employment services can be encouraged, financially and otherwise, to move to a more online, socially connected format that appeals to and more broadly supports our youth.

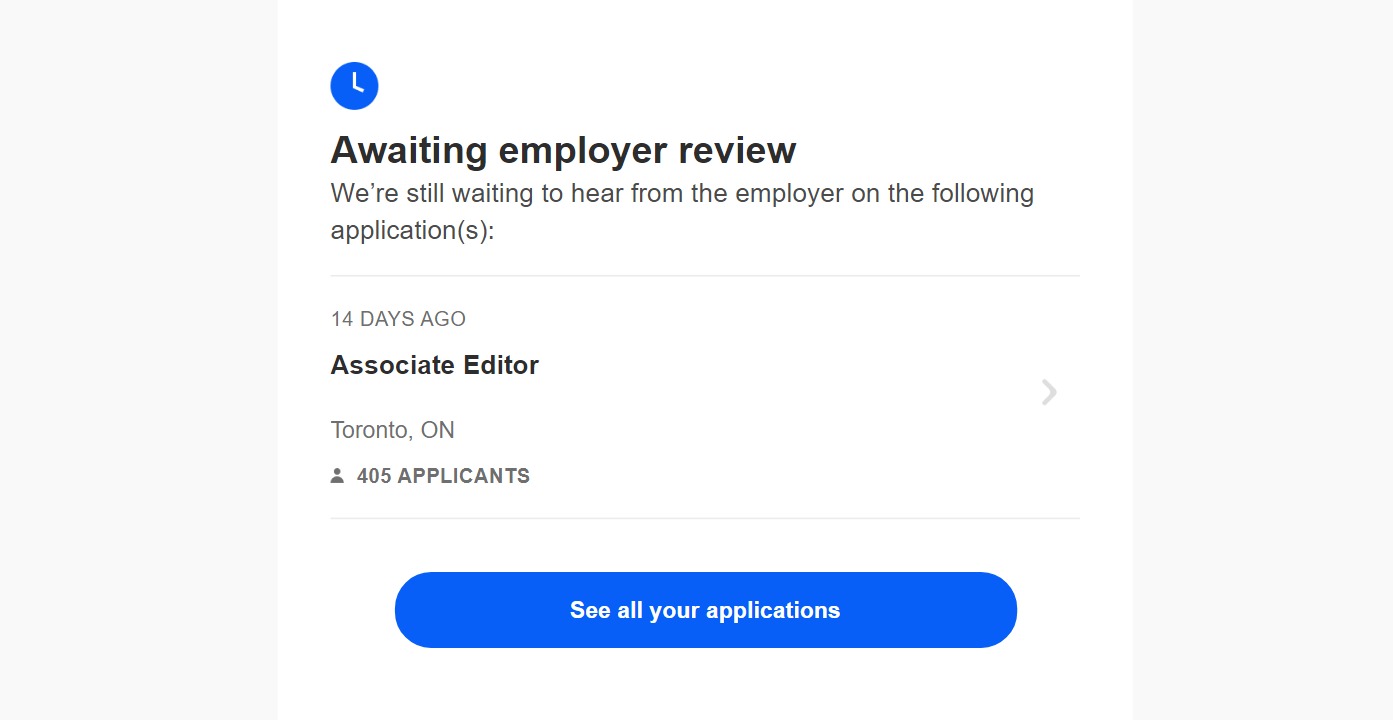

Another possible answer lies in encouraging these same youth to find solutions themselves. One such example is The Graduate Network, launched by two recent graduates. This online service, free to graduates of some of Canada’s top universities, tackles these issues head-on. It helps new graduates cull available jobs to find those that really are entry-level, but will also make use of the expensive, newly-earned degree.

The network also provides support and information about the application process, resumes, and interview tips during a job search. Hiring organizations can post positions with the Graduate Network, knowing the applications will only come from graduates of top Canadian universities.

Initiatives like these certainly don’t solve the whole problem, but along with the coordinated efforts by the government and other creative solutions from a well-educated, highly technically literate generation, there is hope for today’s youth if we take action now.