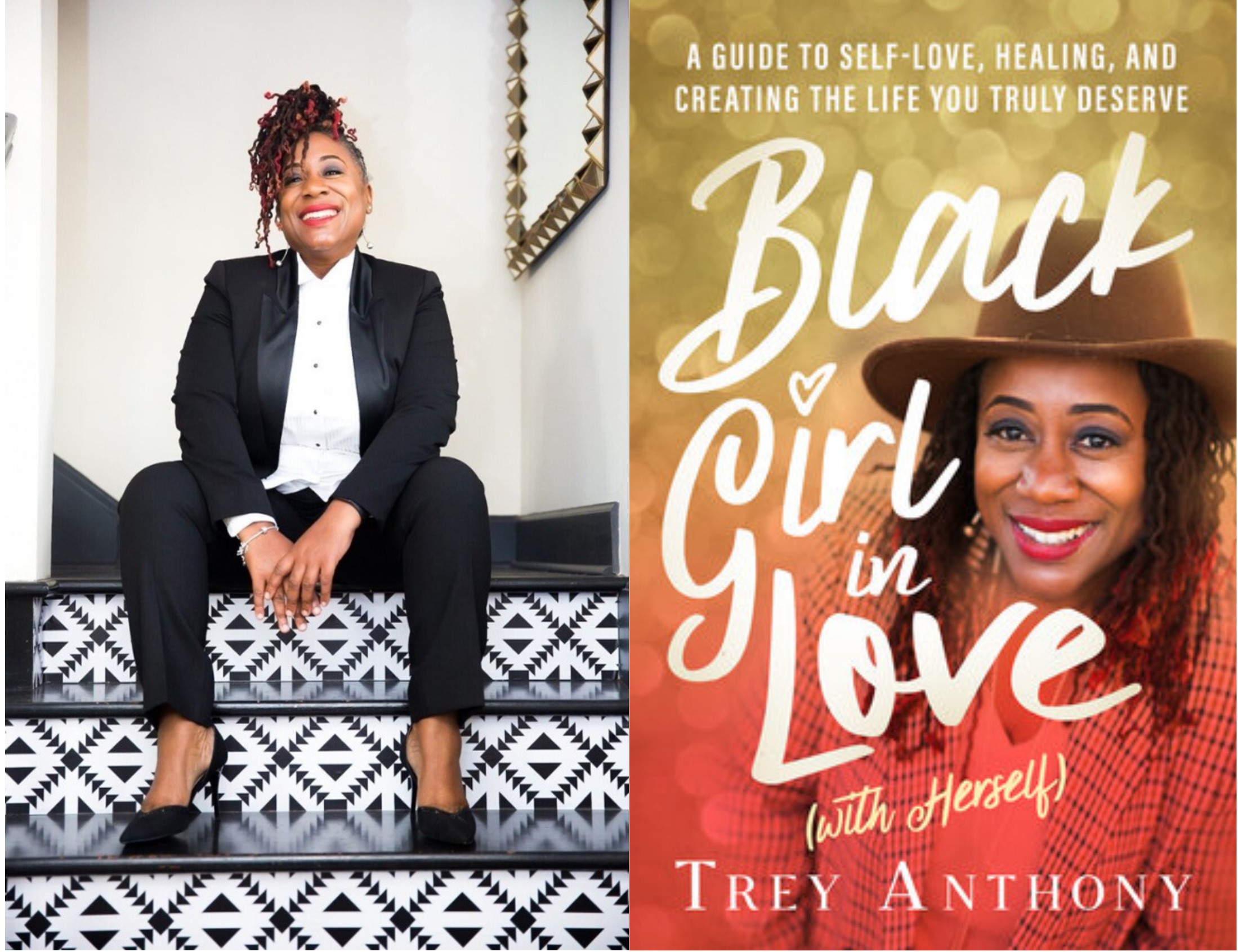

Recently, Excalibur had the opportunity to talk over the phone with award-winning playwright and all-around visionary Trey Anthony. She discussed everything from her early days at York, to the emotional rollercoaster ride that inspired her latest work, Black Girl in Love (with Herself) — a book that’s already landed on must-read lists for 2021, including Essence’s “21 Books We Can’t Wait to Read in 2021.”

Anthony describes the book as part memoir, part self-help guide. With generous doses of her signature humour amidst the deeply personal account of the shocking end of her relationship, she’s candid about navigating the devastation of a break-up while becoming a suddenly single mom to her infant son.

Many remember Anthony for her ground-breaking stage play turned CBC TV show, ‘da Kink in My Hair. Women of colour especially embraced the series for its authentic portrayal of the lives of characters they could identify with. Paula Myers, a York International exchange student alum says: “What I really appreciated about ‘da Kink in My Hair was the joy you could see among the characters. Because our joy matters too. We’re whole people.”

Anthony opened up about what it means to be a Black woman faced with numerous barriers to getting her work produced, and the importance of resilience in creating the life you want. Born to Jamaican parents in London, England, Anthony grew up in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). The Canadian studied at York for three years before accepting a life-changing internship at The Chris Rock Show in New York City. The rest, as they say, is history.

Trey Anthony spoke with Excalibur’s Arts Editor, Carla Lopez, to discuss Black Girl in Love (with Herself).

Q. Can you tell me a bit about your journey so far, as a creative, coming from Rexdale and Brampton, and your time at York, to this point in your career?

A. I grew up in Rexdale, and then I moved to Brampton for high school and that was amazing. Then I ended up going to York for three years and, to the dismay of my mother, I dropped out of school because I got an internship at The Chris Rock Show — the rest is kind of history, right? I’ve always been a huge fan of York. For me it’s always been about being committed to what I felt was my dream and my calling. It’s always been about telling stories rooted in blackness and showing the authenticity of Black women and our various layers. That has always been really important to me, and so I think because I come from that place of truth at all times, Black women trust me with their stories — even women who do not necessarily identify as Black. Black women trust me because they know that I’m going to tell them the truth. I’m also maybe opening their eyes to some realities that they may not be familiar with, so that’s kind of how I see the work that I do — and I love what I do. I’m glad that I’m able to create stories and do what I do right now, you know?

Q. You mentioned your time at York. Did you find that it prepared you for your creative career path?

A. I started out at York and I actually was a sociology and communications major, who also volunteered at the Centre for Women and Trans People. I definitely feel York gave me the lens, especially in sociology, because I didn’t have the language to be able to talk about oppression, class, and race in the way that I was able to afterward. It’s funny, I find every time in interviews people will always assume that I have some kind of university degree or some kind of a Master’s or something — they’re always very shocked! But it’s because I really took that information in — the work I did at the Centre helped me put a name to those things. I think that’s why it shows up in my work, and in that way I’m able to have the language to talk about intersectionality and race, class, gender, and all those kinds of systemic barriers. All that language came from my sociology class. I took a Caribbean Women’s Studies course that Althea Prince taught and it really opened my eyes to Caribbean writers, and that was important for me. So in that class, it really helped root me in the fact that you could write Caribbean stories and have Caribbean-centered work, and that was very new to me.

Q. What were your inspirations or life experiences when you were writing Black Girl in Love (with Herself)? This book seems to be coming from a very personal and deep place.

A. My inspiration really was about saving myself — it was. A lot of people have talked about how personal the book feels, how honest and transparent it is. I wrote the book like the way I wrote ‘da Kink in my Hair — when I was coming out to my family and I was in the deepest, darkest place where my family stopped talking to me because of their own homophobia.

And then I wrote How Black Mothers Say I Love You when my grandmother was terminally ill with cancer and I was really scared about losing her. Then I wrote Black Girl in Love (with Herself) when I was again in one of the deepest, darkest places of my life — when I thought I had found my life partner and I thought that we would be together forever, and that we were committed to each other — that we were to start a family, all of those things.

Suddenly my whole life blew up in my face when I found myself on the bathroom floor after my partner ended our relationship via text message. I had a two-week-old baby and 10 days to vacate our apartment. So, to say it was a shock and my whole life just felt like it blew up is an understatement. I wrote that book to say what happened — how do you get back up from the floor when life does not go according to plan? How do you miss all of those warning signs that tell you that something isn’t as perfect as you want it to be? Why, as women, do we stay in things? Is it because we’re scared to start over and we’re scared to admit when we’re not as happy as we have pretended to be on social media? Black Girl in Love (with Herself) is that book, but it’s also looking at the history of what I had learned from my mother and grandmother about being a strong Black woman, and how I felt looking for a safe place for me — a place to fall apart to talk about the pain and the hurt and the humiliation, and what I felt going through this.

In the book I also talk about my own mental health, being diagnosed with depression and not even knowing that I was depressed because I was so fixated on being strong and getting better and getting over it, that I had suppressed all of these emotions. And when you suppress emotions, it comes out as depression, right?

It has to come out somehow, so that’s what this book is about. It very definitely has a memoir quality to it. But, it also has concrete self-help tips on how to reinvent yourself and cultivate self-care in your life. It also talks about how to set boundaries with your friends and family, and how to set a budget and deal with money. But like everything that I do, it’s personal — very personal. I nearly thought that this was going to break me, but I’m happy to be standing on the other side. I felt compelled to share the lesson of how your mess can become your message and how you can get back up even when you think you’re in your darkest place.

Q. As a Black woman, what are some of the challenges you faced getting your work published? From your plays to your current novel?

A. It’s funny, every single work that I have done has always been met with resistance from mainstream theater, from television networks and publishing houses’ agents. No matter how popular or how many seats you sell or how many millions your show makes, it is still a hard time for me as a Black woman to get my work done. And I’m always met with resistance, you know? Even with this book.

I had to fire my agent because they said, “I can’t sell this book, it’s too niche. Nobody wants to buy this book,” so I ended up firing her and actually going to sell the book myself — and that’s just something I have to do. The same thing happened with How Black Mothers Say I Love You.

Every single theatre company I went to, they said, “oh, it’s too much of a niche story. We can’t sell this to mainstream audiences.” So then I ended up producing it myself until it got picked up. They will code it in language to say, “oh it’s too niche” or “we’re not sure if it’s going to resonate with our audience” and what they’re basically saying is, “it’s too Black.” So mainstream becomes the code word for, “so how can I, as a white person, find myself in your work?” Yet we as Black people, or people of colour, always have to try and find ourselves in someone else’s work.

So for me, I’m very unapologetic about it and I had the whole attitude I think a lot of Black women have — it’s like, “fuck it, I’ll do it myself.” That’s how I’ve gotten most of my work out there and it was the same thing that happened with this book; I went to the publishing houses and I put together the book proposal and I sold it my damn self. I was able to sell it because I didn’t have an agent who held me down.

I think if there’s anything that I would really say to anyone considering a career, be it in the arts or anywhere else, is you better be prepared to be able to do the work yourself, because it’s never handed to us as people of colour. It’s never handed to us.

Trey Anthony’s Black Girl in Love (with Herself) is available now in bookstores.