Hassam Munir | Executive Editor (Online)

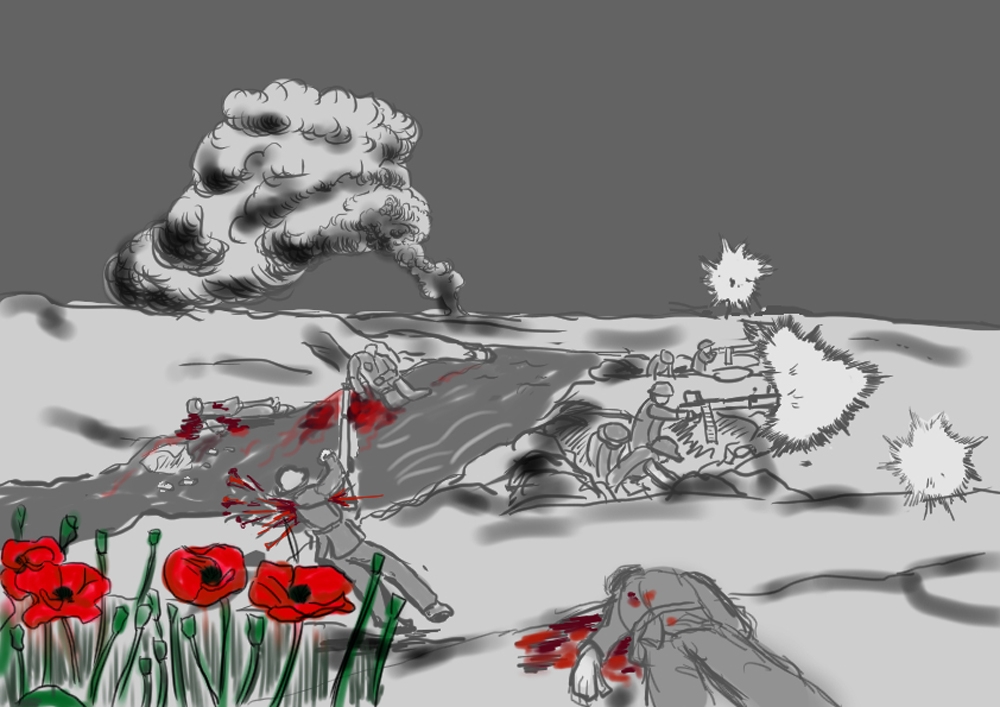

Featured illustration by Cedric Wong

“What happened, what we recall, what we recover, what we relate, are often sadly different. The temptation is often overwhelmingly strong to tell it, not as it really was, but as we would wish it to have been.”

Bernard Lewis, a centenarian and one of the preeminent historians of the Middle East, encapsulates my thoughts on Remembrance Day in these words written nearly half a century ago.

The past, history and heritage are three very different things. Think of the past as a city, like Toronto. History, in this example, is a map of Toronto, which outlines and represents the city but can never fully capture all of its detail and vitality. And heritage is a map of Toronto in which all the areas and features of the city that we don’t value have been erased. Those that are left have been jumbled up in the way that makes Toronto—to borrow an expression—great again.

Remembrance Day is an exercise of heritage. This is not to say, of course, that it has nothing to do with history or the past. The date itself reminds us that 98 years ago on November 11, the bloodiest war in human history up until that time finally came to an end. It’s unfortunate that I have to specify “up until that time,” but the worst was yet to come and in many ways, the old saying has proven prescient: only the dead have seen the end of the war.

As a history student, I am keenly aware of the importance of not looking arrogantly at the past from the privileged position of the present. We should not presume why thousands of Canadians have served and sacrificed so much in distant parts of the world, taking on roles in conflicts ridden with horrific atrocities and a staggering combined death toll of at least 80 million.

But I’m also aware of the dangers of historical amnesia, the act of collectively forgetting certain aspects of our history. The past does not repeat itself; we repeat the past by failing to take a honest and critical look at our history. It is wrong to presume, yes, but it is necessary to question.

And this is the crux of the problem with the ritualistic observances of Remembrance Day. Whether by design or by coincidence, it does not encourage us to check our blind spots, to question our exclusionary and feel-good narrative, and to invest time and effort into contributing the best that we can offer toward creating a more just and peaceful world.

It encourages us to wear the poppy, to donate funds to support veterans and, every year, to take a few moments out of one day of our otherwise-disengaged lives to remember those who have served and sacrificed so much for us.

And that’s not enough. Injustice and conflict are widespread, including right here in Canada, and it will take our own service and sacrifice to find ways to tackle them without repeating the chaos and brutality of the previous century.

Lest we forget, but more importantly, lest we regret.