Jenny Mao | Copy Editor

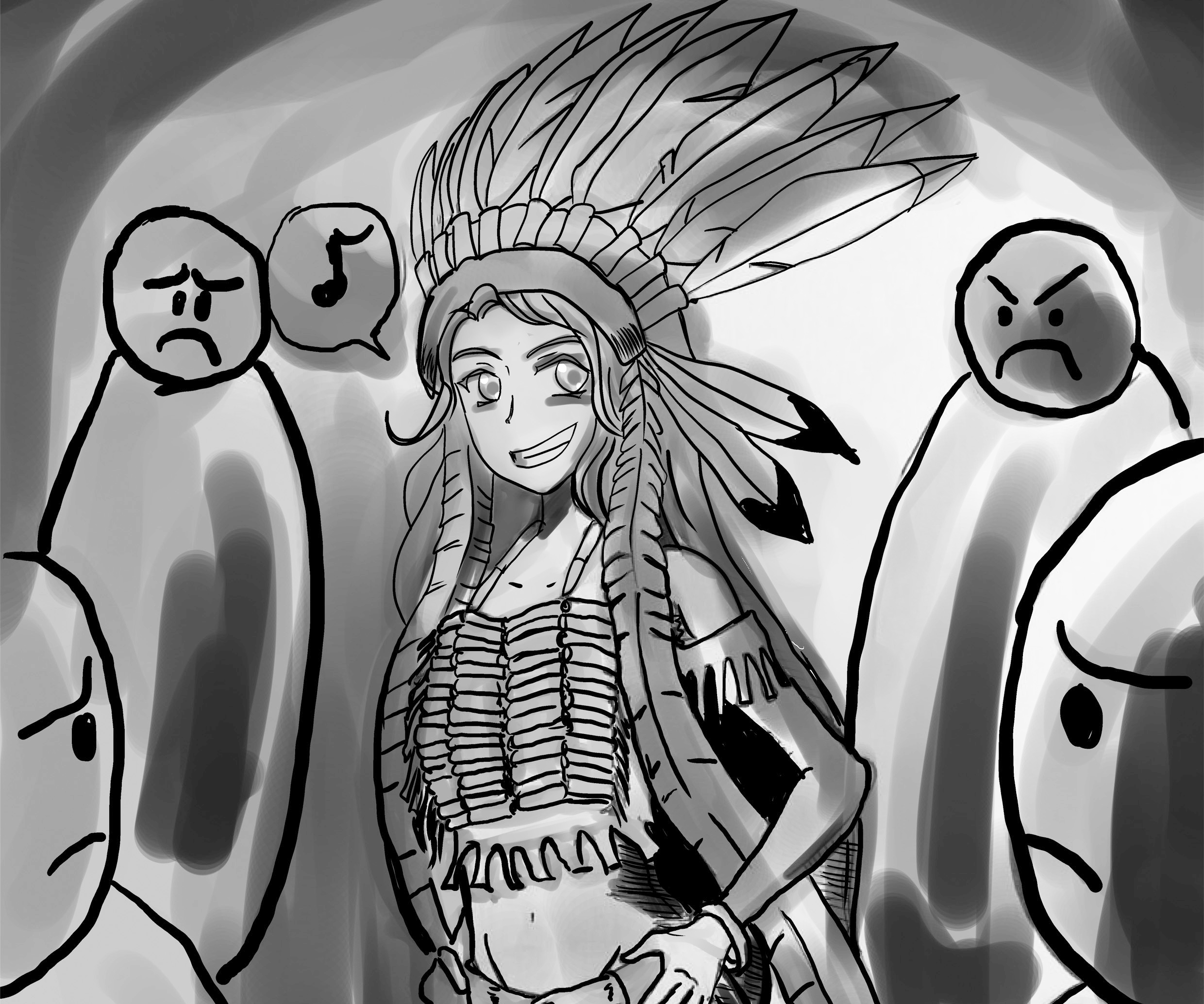

Featured illustration by Cedric Wong

Halloween is supposed to be the one day of the year where you are welcome to become someone else without drawing unwelcome attention. You are welcome to dress to your wildest imagination, welcome to wear bold costumes and welcome to become a person who could never be the real you the other 364 days of the year.

But where is the line drawn between welcomed and unwelcomed costumes?

Some people would say there is no line, and if you want to dress as a Indigenous person, geisha, Mexican or in blackface, you should go right ahead.

But those are problematic and prime examples of cultural appropriation.

Cultural appropriation is taking parts of a person’s culture without being a part of it, through symbols, clothing, words or practices. It tends to occur more during Halloween, like when dressing up as the racial identities previously mentioned. By doing so, you are taking the nice and fun aspects of a person’s culture without experiencing any of the hardships.

I once worked at a party store in which the Halloween season was equivalent to a mall’s Christmas. While all the typical and popular costumes of superheroes, princesses and various occupations were chosen by both children and adults, there were many customers that would ask for the “Indian costume” or the “sexy nun costume” without even blinking an eye.

While some customers would half-heartedly joke that the sexy nun costume was horrible, very few saw issues with dressing up as an Indigenous person—or that the costume name incorrectly and racistly labelled Indigenous groups as “Indian.” It also didn’t help that there was an entire section dedicated to Indigenous costume accessories, including Native American headdresses that were traditionally constructed by individual feathers earned through acts of bravery.

A non-Indigenous person wearing Indigenous clothing and accessories such as a headdress is appropriation. As the appropriator, none of the consequences faced by Indigenous people affect them. For the appropriator, it is a costume that can be taken off at the end of the Halloween party.

But for Indigenous people, it stays with them as it is a part of their life and culture, even after they have taken the clothing and accessories off.

There’s always that argument that a person wasn’t intending to be racist with their costume choice. But just because you didn’t intend to be racist doesn’t mean your costume is not racist. Perhaps you don’t see it as racist because the identity or culture’s struggles don’t affect you, and by wearing these problematic costumes, you are reducing racial identity to the most basic stereotypes.

We dress up as characters in costumes during Halloween for the sake of fun, laughs, memories and, sometimes, to look risqué. In this context, costumes are worn for the sake of show, not to represent the struggles or history of specific cultures or races.

So please, this Halloween weekend I welcome you to become the character of your wildest imaginations, but please make sure your costume isn’t problematic. That would be unwelcome.

A piece of ertiouidn unlike any other!