Insite, a safe injection site in Vancouver, has contributed to reducing overdose deaths and the spread of HIV through medical supervision

Melissa Leone

Contributor

Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside has long been known as a hotbed for drugs and disease, with average life expectancy of its residents in 1996 a full nine years below the provincial average. At one point, AIDS was spreading so fast among intravenous drug users, and overdose death rates were so high, that the local health board had to declare a public health emergency.

That’s why recent statistics from Vancouver Coastal Health, which say that life expectancy in the area has jumped to just two years under the provincial average, are simply astounding. At the core of this incredible development is the harm reduction work of one unique organization.

Located in the Downtown Eastside neighborhood, Insite has been providing a safe and health-focused space for intravenous drug use since 2003.

The protocol at Insite is simple: addicts bring their own drugs, and use them in one of 12 injection booths. This takes place under medical supervision, every day of the year from 10 a.m. to 4 a.m.

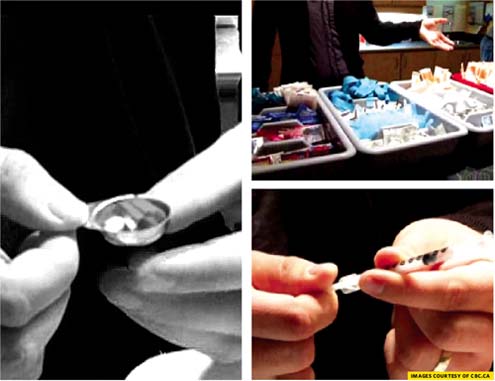

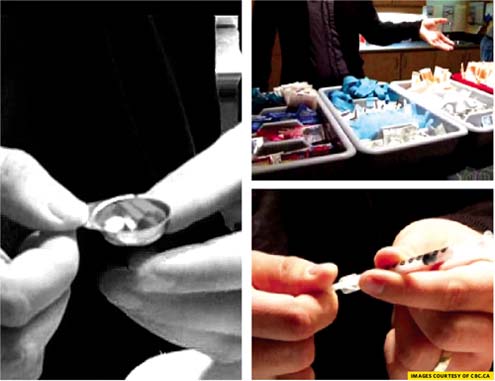

The site is full of clean needles, sterile water, cookers, filters, tourniquets, alcohol swabs, and condoms. Patients are in and out of Insite in 15 minutes or less, and the wait time averages between 20-30 minutes.

At the site, patients are exempt from the criminal code, and cannot be arrested as long as they are using drugs inside the building.

Carol Strike, associate professor of public health at the University of Toronto, has done extensive research on harm reduction. Stike says there is an informal agreement between the workers at Insite and drug dealers that dealers can sell drugs within a one-mile radius of the building.

There are always staff on duty at Insite. Two nurses stand by with oxygen masks and syringes of the overdose drug, naloxone. To date, 1,500 overdoses have been reported at the site, but because of quick intervention by Insite’s medical staff, there has not been a single casualty.

Insite also has addiction counselors, mental health workers, and peer staff that connect clients to community resources such as housing, rehabilitation, and other support services.

Insite has over 12,000 registered drug users and sees an average of 850 visits a day. All patient information is kept confidential, as patients use code names to enter and exit the building. Most patients are homeless or barely housed, and have legitimate mental health issues.

Strike found that 70 per cent of Insite’s patients are males in their late 40s. An average patient at Insite has been using for over 16 years.

The philosophy of Insite is simple: If intravenous drug use is going to occur, a space that alleviates its dangers is a must. The risks of unsupervised injection are high, as drug users are often hurried, and are less likely to have hygienic equipment.

For example, addicts are known to mix their drugs with puddle water, or doing “shake and bake,” which is mixing the drugs in the syringe without first cooking out their impurities. Such techniques can cause gangrenous abscesses and endocarditis, a bacterial infection of the heart valves.

At Insite, this danger is eliminated as users are given a tray of instruments upon entering, which contains clean syringes, adhesive bandages, and antiseptic pads. All products are tossed out after one use, and nothing is recycled.

Since opening, Insite has taken drug users off city streets, and reduced the spread of transferable disease in Vancouver, including HIV. In 2008, Vancouver’s overdose deaths were the lowest in 30 years, and the rate of new HIV infection among injection drug users was the lowest since record-keeping began in Canada over 30 years ago.

Insite currently costs just three million dollars a year to run out of Vancouver’s 44-million dollar budget for addiction services.

When the Conservative government came into power, harm reduction was taken out of its national drug strategy. Prime Minister Steven Harper was on a mission to close down the facility, believing it to foster addiction and relapse. He was also fundamentally opposed to the idea of the site’s funding coming from taxpayers, a criticism echoed by many Canadians.

Fortunately for Insite, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that closing the site would violate the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The facility was allowed to stay open, sparking interest in several other Canadian cities, including Victoria, Ottawa, Toronto, and Quebec City, to open safe-injection clinics of their own.

But support for a Toronto version of Insite is far from unanimous, even among drug users.

A group of young men sitting in the lobby of Vita Nova, a non-profit organization located in Vaughan that provides support for different forms of addiction, collectively agree that opening such a site in Toronto is a bad idea.

Luciano, an ex-heroin addict, says the idea is too tempting.

“I’ve been here more times than I’d like to admit. I was sober for years, and then you get a craving, the smallest craving in the world, and before you know it, you’re using again,” he says. “To me, Insite sounds like a wonderful place to relapse at, and I don’t want to relapse again.” The other men nod in agreement.

“I understand why people think this is helpful, and trust me,” says one of the men. “It sounds really appealing to me, almost too appealing, and that’s why they shouldn’t go through with it.”

Franca Carella, founder and executive director of the Vita Nova Foundation, passionately opposes the idea of introducing a safe injection site to the city.

“It makes me sick. I would never support a site like this opening in Toronto. Allowing addicts to use in a place like this is basically an open invitation for death,” says Carella. “I will not help people die.”

She mentions that a recent University of Toronto study proved addiction has an 82 per cent curable success rate, and that this success rate is achievable for any addict. Sites like Insite will only worsen the possibility for recovery, she says.

“The money used to fund this clinic should really be put towards prevention, treatment, enforcement, and harm reduction,” says Carella. “We need to help addicts heal, help them discover their dreams and their goals, allow them to transition from a life of pain and sorrow to happiness and hope.”

On the other hand, Strike, who has been studying the possibility of a similar site in Toronto, says the sites themselves would be tools in harm reduction.

She recommends building up to three safe injection sites in Toronto, and two in Ottawa. To minimize attention drawn to them, and to ensure privacy and confidentiality, she reccommends integrating them into rehabilitation establishments already existing in the city.

Through her study, Strike found that over 50 per cent of Ontarians agree Toronto and Ottawa need these sites.

However, there is no guarantee that a safe injection site will have the same effect in Toronto.

Anna Marie D’Angelo, senior media relations officer at Insite, says the culture around drugs in Vancouver is different from that of Toronto.

“We never advise others what to do. All we can say is that Insite works in Vancouver because it is set up in a location with a history of intravenous drug users,” says D’Angelo.

Many people believe overcoming drug addiction is simply a matter of willpower and dedication. Most experts agree addiction is a brain disease, and though recovery is challenging, it is certainly possible.

Unfortunately, recovery is not an option for everyone. Countless addicts refuse or fail to complete treatment.

Insite has approached what it sees as an inevitable problem, and is working towards mitigating it instead of trying to eliminate it. Perhaps it’s time Toronto started thinking the same way.