What you need to know about last week’s solar storm

Nathan Malcolm de Rushe

Contributor

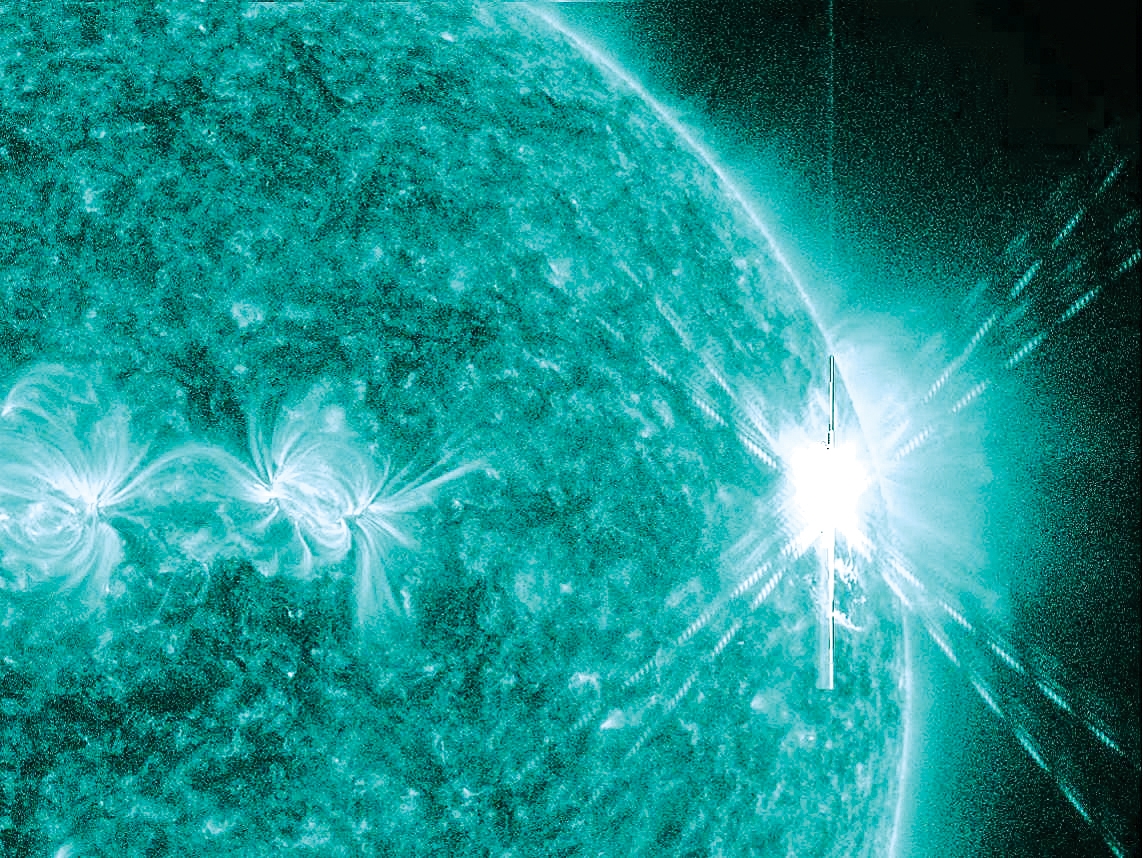

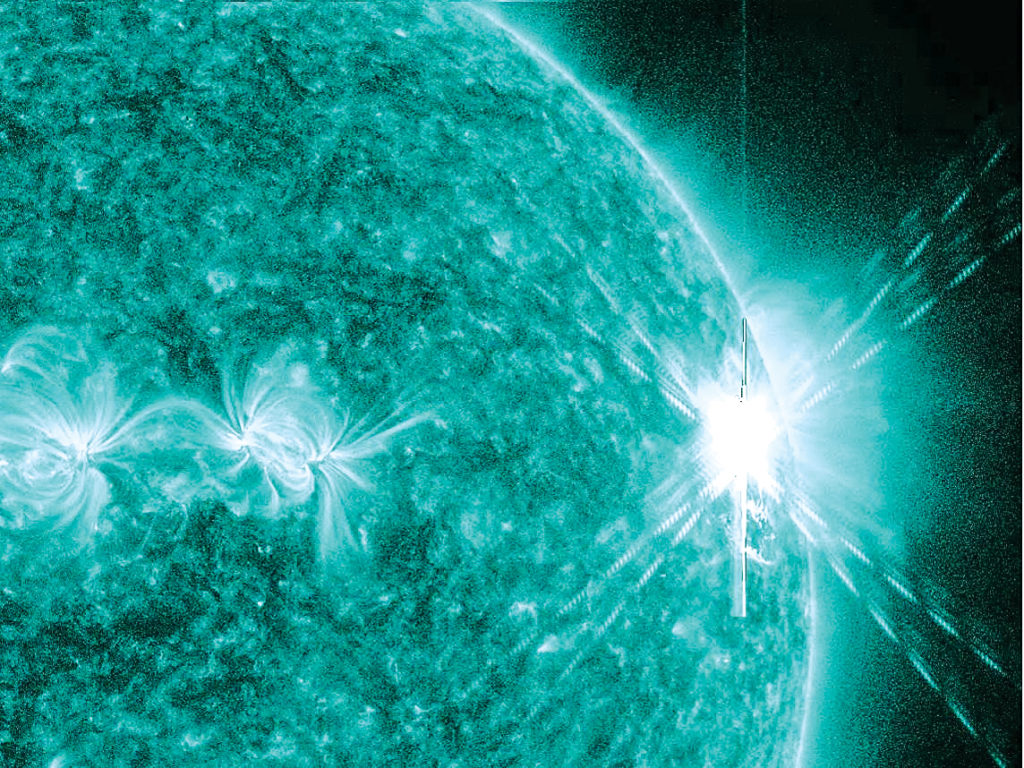

Last week, Earth was hit by a massive solar flare.

Magnetic energy erupted from the surface of the Sun, releasing an enormous cloud of superheated gas and charged particles. Known as a giant Coronal Mass Ejection (CME), the cloud hurled towards the Earth at 4.8 million km/h, reaching Earth in 35 hours.

CMEs can cause electrical disruptions to power grids, damage orbiting satellites, and interfere with GPS signals, radio communications, and airline flights.

Solar flares interfere with the way our communication satellites work. Jesse Rogerson, a PhD candidate in astronomy at York, explains that most communication satellites bounce signals off parts of the atmosphere.

“When a solar flare [happens] and the charged particles are going through parts of our atmosphere,” Rogerson explains, “it can hinder the bouncing, making it difficult to create communication that way.”

With this in mind, many airlines with North Pole flyovers routed their planes to avoid communication disruptions and damaging electromagnetic radiation.

Many power stations across the country were on high alert for potential impact from this solar storm. After-effects from a solar flare can cause mass blackouts, like in Québec in 1989.

Despite the possible negative effects, this solar storm sure did create a magnificent sight for watchers of the night sky. Residents of Ireland, Scotland, Norway, and northern Canada had a spectacular view of the aurora borealis.

The aurora borealis is caused by the atmosphere colliding with charged particles released by the sun. At the height of the recent solar event, the northern lights were the brightest they have been in years.

The Sun is reaching its “solar maximum,” a peak of solar activity that occurs every 11 years. It is expected to occur sometime between 2013 and 2014. This means similar, yet fiercer solar storms could be heading our way. The strength of possible upcoming storms is unknown, as solar flares are very hard to predict.

Solar flares are measured in classes, A, B, C, M, and X. These classes are broken down into a scale of one to nine, with each energy increasing tenfold. X class flares have no caps on its scale. This solar flare was classified as M9, on the verge of becoming an X-class.

The most powerful solar flare recorded occurred in 2003, where it became so powerful it overloaded the sensors monitoring it. After X17, the equipment malfunctioned. The flare was later estimated to be X45.

X-class solar flares are extremely dangerous because they can severely damage satellites, create massive radiation storms in the North Pole, and potentially cause world-wide black outs.

It’s hard to speculate about future X-class solar flares, Rogerson says. Our knowledge of the Sun is limited.

“We’ve been studying the Sun like this for 50 or 60 years,” Rogerson goes on, “but the Sun has been around for 5 billion and will be around for another 5 billion.” He says it’s difficult to tell what the Sun is going to do during any given year.

“It’s certainly possible that we could have an X-class [solar storm],” Rogerson says, “but its definitely not guaranteed.”

For now, NASA will do its best to track flares. The Solar Dynamics Observatory is an unmanned spacecraft that studies the Sun. Launched in 2010, the instrument can help predict and track solar activity, hopefully warning us of severe solar events in the future.

Solar flares, past and upcoming, won’t cause apocalyptic destruction. Our knowledge of the Sun and solar flares, while small, is increasing. Hopefully scientists will be able to predict X-class solar storms in the future. Until then, the answer is blowing in the wind.

With files from National Geographic