The new crank-style lomography motion camera aims at consumers bored by digital video

Ernest Reid

Science & Technology Editor

Shane Fester might make a silent skateboarding movie—think Spike Jonze meets Charlie Chaplin—but doesn’t know how to start it.

“I’m really intrigued by the concept of a silent movie,” Fester says. He admits his exposure to silent film was limited while he studied at OCAD. With the new LomoKino, that’s going to change. Now, he says, he can make a mini skate movie on one role of film.

“If silent film returned,” Fester continues, “that would be incredible.”

Fester is the store manager of Lomography Toronto. They recently launched the new

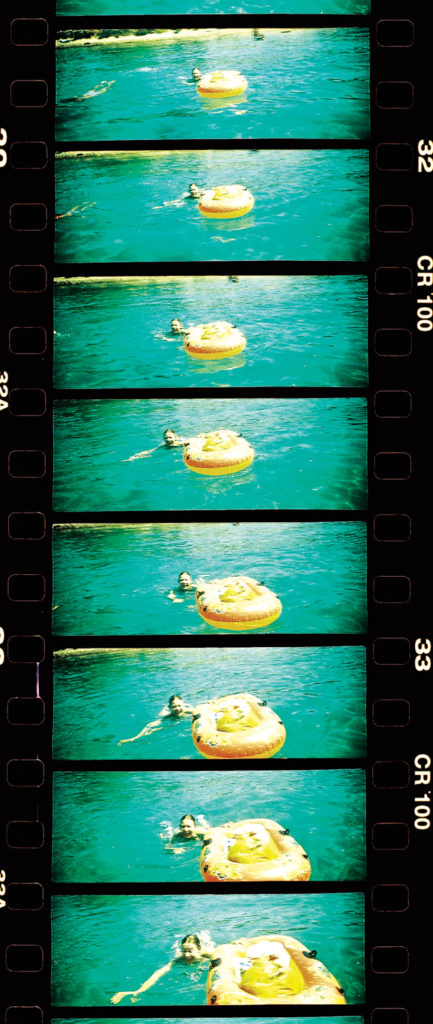

LomoKino, the first camera to make lomographs move on 35mm film. The camera uses a classic crank-style design to capture 144 shots on one roll. The lomography movies are silent, and last 36 to 48 seconds long.

Fester says the technology’s been standard since the end of the silent film era and he’s excited that it’s coming back.

“It’s not the highest technology you can use, [but] it’s going back

to what people used to use.”

He thinks we’ve lost something in the move to digital technologies. He says a lot of people come into the store and don’t understand why people would return to film. They’re always surprised when he says film never left.

“You limit yourself when you choose to shoot all-digital,” Fester continues. The experimental

quality of physical film is amazing, he says, and camera operators can’t afford to miss out on that.

There haven’t been a lot of options for physical film enthusiasts. Photographers and filmmakers can’t use analogue photography and film, Fester says, because their corporate clients often expect high-definition quality video. HD is the standard now.

But people forget that using 35mm is a standard, the manager points out. They stopped making other types of microfilms because 35mm was “the best”.

Fester says he’s shot 35mm on a lot of the cameras in his shop and blown them up wall-sized. “I’ve gotten no complaints about quality, but to each their own I guess.”

The LomoKino is designed knowing people have basic film software. They know consumers will get their shots scanned, digitized, and looped on iMovie. It mediates a desire for an older, washed-out look using digital platforms.

You get the effect as you’re taking the picture; you won’t know what happened until you develop the film.

Jake Meyer, a New York photographer and graphic designer, thinks there’s something precious about this process. He’s considering using the LomoKino in his professional work.

“It’s not like digital, where you can snap off 30 [photos] and go through it and go ‘oh, I got a good one.’”

Digital technology takes the art away from what he does, Meyer says, because anyone can take a good photo these days.

He says analogue photographers are a dying breed, but photography’s become boring now that everything is in HD.

People’s boredom with high-definition and digital is why shops like this—Meyer gestures around—are thriving.

Before Ashley Ang joined Lomography Canada, all she knew was the digital side of photography.

“Before I started working here I didn’t know about film,” she laughs. What attracted her was Lomography’s organic feel. “It’s very raw,” she says.

On digital technologies, you can take pictures and films and adjust accordingly in post-production. The LomoKino project works against this. The tecnology is designed for no sound, no special effects, and no post-production—just lomography in motion.

Lomography in motion brings the aesthetic to another level.

With the LomoKino, “there’s

the reality to it. You can’t hide from it,” she says, “but that’s the cool part.”

Ang says being a throwback is never a problem. The LomoKino has old aesthetics coupled with modern functionality.

“We’re going into your mother’s closet for an old sweater—we’re sort of doing that, but cool.”

With files from Lomography Canada and Mark Dyer